The F Pawn

The Story of Michael Aigner

Hello, chess readers!

Originally, my plan was to write about my experiences playing chess at my local senior center and club, and include a few of my games and my analysis. That post is still on my to-do list, but for now, I want to talk about something else. Something that I consider much more important.

The idea for this blog all started on just a normal morning. I was watching an old Hikaru speedrun video (around the 10-minute mark) and eating breakfast, only half listening, when Hikaru said something that caught my attention. He was playing an opponent called “fpawn,” who he explained was Michael Aigner, someone who suffered from quadriplegia, meaning he has no arms or legs. The moment I heard that, I was intrigued. Hikaru went on to say he had met Michael in person and that he was one of the most optimistic and genuinely kind people he had ever met.

I was stunned. I consider myself an avid chess player, writer, and all-around fanatic, but I had never once heard of this inspiring figure. It reminded me of a movie I once saw about Bethany Hamilton, the “Soul Surfer” who lost her arm to a shark attack. Her story became famous not just in the surfing world, but far beyond it. Yet in the world of chess, Michael Aigner’s inspiring story remained largely unknown. If even I, a lifelong chess fan, hadn’t heard of him, how many others were missing it too? So I am now going to use this blog as an opportunity to change that, to share the story of an incredible chess player and an even more incredible human being!

Who is Michael Aigner

To start this blog, I want to give everyone reading a little more information on Michael Aigner. As soon as Hikaru introduced me to Michael, I did what any sane person would do: I started learning everything I could about him.

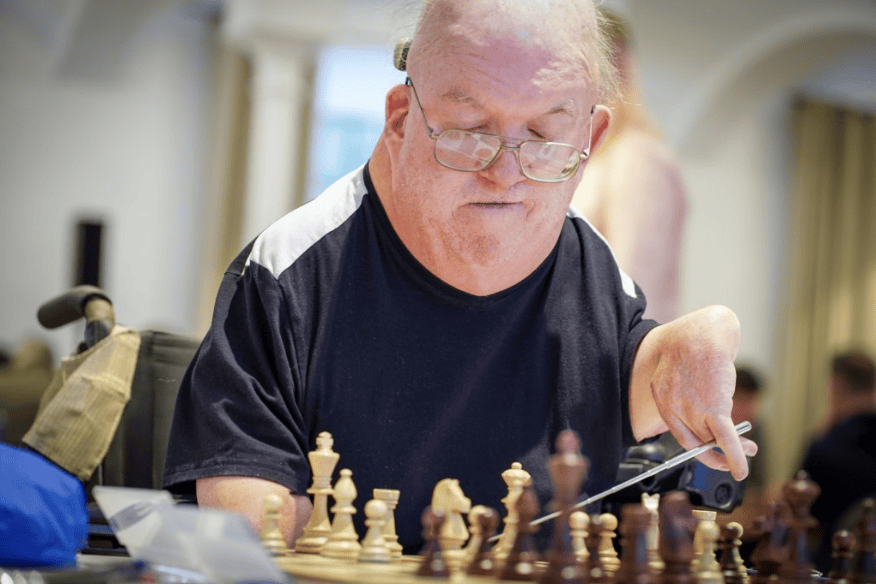

In my research, I found that Michael Aigner was born in Munich, Germany in 1974, but was actually born with quadrilateral phocomelia. This condition causes his arms and legs to be extremely shortened, and as a result, he has to use a wheelchair for mobility. Contrary to what Hikaru described, Michael is not a quadriplegic. Quadriplegia refers to paralysis, which is different from Michael’s condition. More importantly, I learned that Michael is so much more than this condition.

Michael moved from Germany to the United States in 1980, shortly after turning six. He discovered chess a year or two later and quickly developed a love for the game, all the while excelling in the classroom. After he finished high school, he moved to Northern California to attend the University of California, Davis, where he earned highest honors in Mechanical Engineering with a second degree in Mathematics.

It was during his time at Davis that Michael truly entered the competitive chess world, joining local clubs and playing his first rated tournaments. He later attended Stanford University for graduate school, earning a master’s degree in Biomechanical Engineering. While there, he competed for the Stanford chess team in major collegiate events, traveling across the country to face some of the strongest programs in the nation.

Even back then, Michael’s passion for chess was clear. He was not only competing at a high level but also already showing signs of the aggressive and sharp play that would define his career. Over the years, he has achieved remarkable things both on and off the board, which I will highlight in the fittingly named Accomplishments Both On and Off the Board section.

Overcoming the Odds

Michael Aigner has never let circumstances get in the way of his chess. Despite being born with quadrilateral phocomelia, and having to use a wheelchair, he has found ways to thrive both over-the-board and online, even in fast-paced time controls like blitz and bullet.

Michael has said that his disability doesn’t really affect his chess play. The only difficulty he faces is sometimes reaching pieces across the board, though he uses a stick to make that easier.

His bigger challenge comes in fast time controls, where he occasionally runs into time trouble. As he put it: “I love to play blitz. Unfortunately I am also a slow blitz player. I obviously lose games on time or because of time. I would never play 1 minute bullet, although I do online. So in that regard my disability does limit me a little bit.” (Perpetual Chess Podcast, 39-minute mark).What’s even more impressive is how little he dwells on it. When I listened to his interview on the Perpetual Chess Podcast (starting around 4:45), what struck me was that he never frames his condition as a sob story or an excuse. He only talks about it when prompted, and even then it’s in a straightforward, “it is what it is” manner. It’s clear he wants people to focus on his chess and contributions to chess, and not his circumstances. In most of the podcast, and in other interviews I listened to, he simply talks about chess, whether it’s games he has played, students he has coached, or just the game in general. You can tell he truly loves the game, and his optimism shines through. As Hans would say, he lets his chess speak for itself.

In fact, the biggest challenge to his chess in recent years hasn’t even been phocomelia. Over the last decade, he’s developed a neurological condition that makes long-distance travel difficult, which has limited his ability to play in major tournaments outside of California. Despite that, he remains deeply active in the game, constantly coaching and competing throughout the state.

Accomplishments: Both on and off the board

Throughout this podcast I also came to realize how truly incredible Michael Aigner is as a player and coach. His peak USCF rating hit 2341, and his FIDE rating reached 2298, earning himself the title of National Master as well as the US Chess Life Master title. He has also competed in major national tournaments, including taking second place at the 2006 U.S. Open, which earned him an invitation to the 2007 U.S. Championship. On top of that, he has scored over-the-board wins against numerous top grandmasters like Igor Blatny, Alex Yermolinsky, Varuzhan Akobian, and even Daniel Naroditsky. This is what Michael considers his best game, a win against GM Alex Yermolinsky.

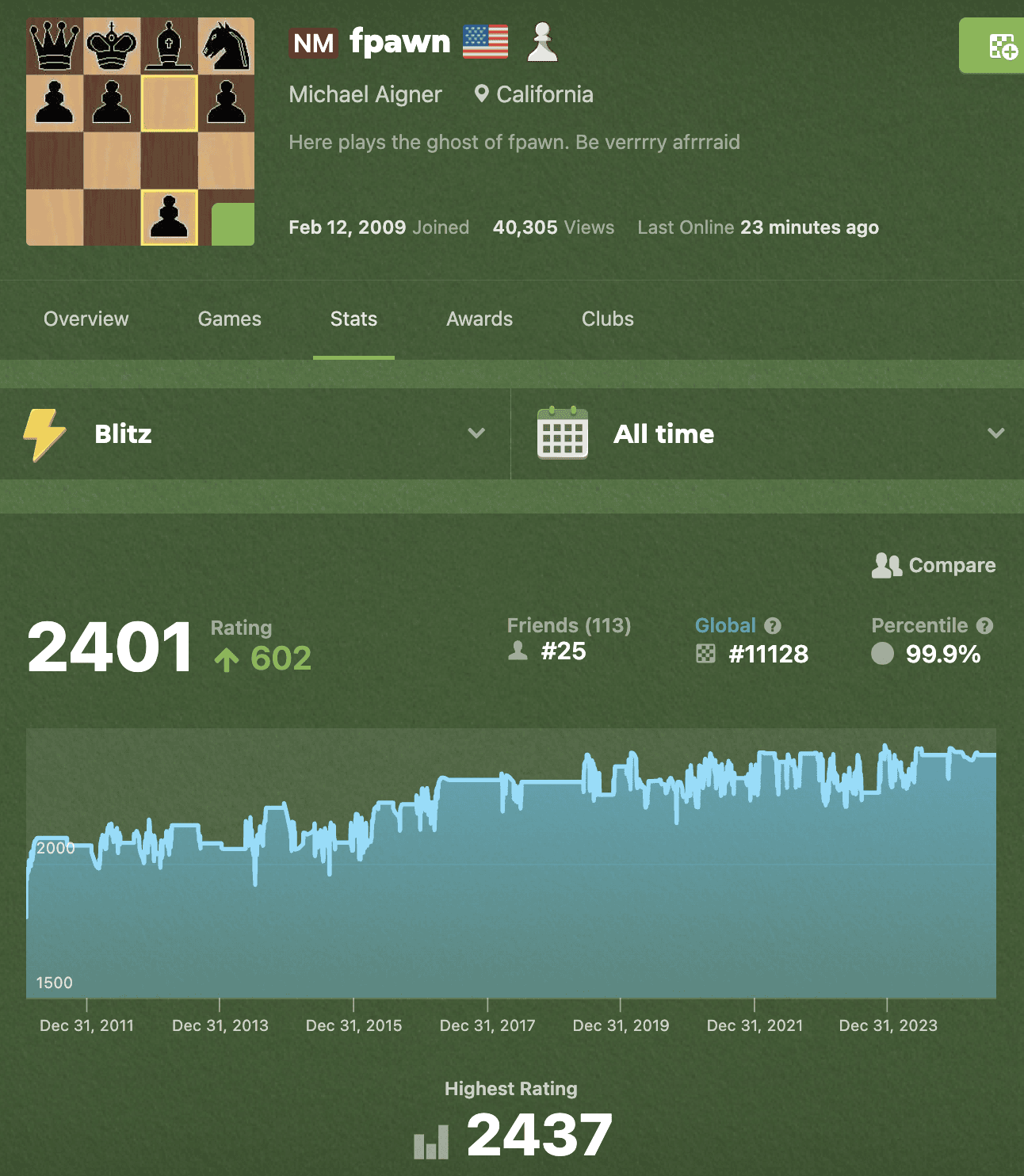

Michael has also dominated chess online, reaching a blitz rating of over 2400 on Chess.com, placing him in the top 99.9 percent of all players on the platform.

You can also see from the fact that he was online 23 minutes ago, that he still is very active in the chess world, constantly playing and participating in events. What really stands out is his style. His play is very sharp, aggressive, and full of tactics, in a way that almost reminds me of Mikhail Tal. This is a fairly common strategy for online blitz, but he has also dominated long form over the board tournaments with this razor sharp play. And he hasn’t slowed down at all. Michael now holds the title of FIDE Trainer, and continues to work with advanced junior players across California. On top of coaching some of the nation's rising stars, he still finds time to represent the United States. Just five years ago, he played Board 1 for Team USA at the 2020 Online Olympiad for People with Disabilities.Why fpawn?So why does Michael call himself “fpawn”?The answer is actually pretty simple. Michael just really enjoys openings where the f-pawn starts marching up the board right away. As White, that usually means the Bird Opening (f4). As Black, it’s the Dutch Defense (d4 f5). Both are sharp, aggressive, and just uncommon enough that a lot of opponents will find themselves thinking, “Wait… what exactly am I supposed to play against this again?” Here is a phenomenal game Michael played with the Dutch Defense against Eric Schiller in 2004.

For readers who might be newer to chess, this approach isn’t just random. At higher levels, it’s very common for players to choose unusual or offbeat openings to throw their opponents out of preparation. In other words, they’re aiming to drag the game into unfamiliar territory. The difference with Michael is that he isn’t just doing it as a trick — he actually thrives in these positions, always finding creative moves and keeping his opponents on edge. Oftentimes that means launching a massive attack to checkmate the king, or he will use the attack to trade into a winning endgame. As Michael likes to put it, “When you have a winning position, K.I.S.S.: Keep It Simple, Stupid.”

Takeaways

If there’s one thing I’m taking away from learning about Michael, it’s that excuses are overrated. The guy could sit around saying “Well, chess is too hard with my condition” and nobody would blame him, but instead he’s out here crushing grandmasters, coaching future superstars, and basically running half the chess scene in California. Watching how he plays and participates in the world of chess makes you realize that talent matters, yeah sure, but your attitude and mindset are the things that really determine how far you’ll go. Also, if he can show up every day, give his best, and make an impact despite the challenges he faces, then the rest of us have truly no excuses.

Conclusion

Thank you so much for reading my blog! I really tried to write in a style that matches my usual speaking tone and cadence. I want to thank the judges for the phenomenal feedback they gave, not just to me, but to every single participant, which I think is truly amazing. I also want to acknowledge everyone who helped make this post possible, starting with Hikaru, followed by the Perpetual Chess Podcast and Kirk Ghazarian, and finally Michael Aigner himself. Michael, if you are reading this, I want you to know that you are a huge inspiration, and I wish you the best in the rest of your chess journey!